Introduction

When the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) Spinraza (nusinersen) in 2016 to treat spinal muscular atrophy, it generated a lot of enthusiasm among patients and pharma companies alike. It was the first drug to treat this fatal and previously ‘undruggable’ genetic neurological disorder. In the same year, the FDA granted accelerated approval to another ASO drug, ExonDys 51 (eteplirsen) to treat one more intractable genetic disease, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). The approvals rejuvenated new interest in oligonucleotide-based drugs, as evidenced by a large number (>180) of ASO candidates in active clinical trials worldwide1 . These candidates are meant to target a myriad of diseases including cancer, viral infections and several genetic disorders.

The concept of antisense oligonucleotides was, however, first demonstrated as early as in 19782 when scientists showed that short single-stranded synthetic oligonucleotides could modulate RNA functions. The idea was well-received because of the overwhelming simplicity that any disease-related RNA can be targeted solely based on genomic information to alter protein expression, even when traditional small molecules may not be amenable. The next four decades have witnessed a vast development of the field, in terms of new chemistries, targeting mechanisms, pharmacology, and delivery strategies3 . Notably, the technology of silencing RNAs which can be classified as a double-stranded ASO resulted in a Noble prize being awarded in 2006. The initial hope and hype have, however, mostly waxed and waned because of various reasons like unsatisfactory cellular uptake and stability, off-target effects, and high costs. Before 2016, three more drugs (fomivirsen, pegaptanib, mipomersen) were approved by the FDA but none of them attained commercial success. Despite these setbacks, the case of ASOs is stronger than ever before because of recent advances in understanding the genetic basis of human diseases and predictable potential to correct faulty protein expression by non-conventional means (e.g., splicing modifications)4 .

Antisense Structural Types

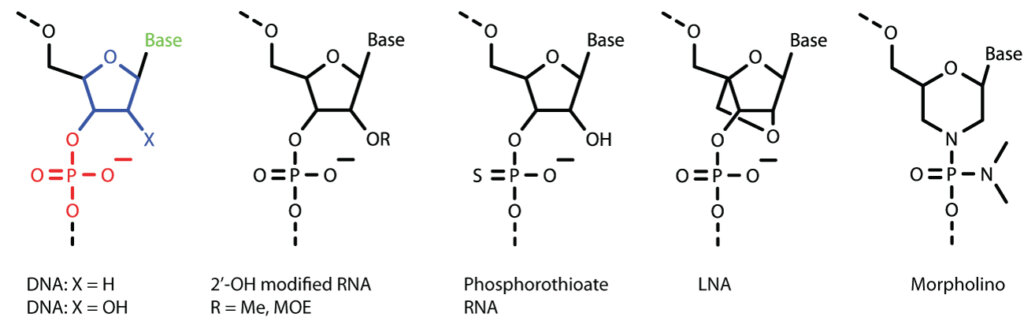

Antisense oligonucleotides are short (15- to 30- mer) synthetic oligonucleotides that are chemically modified and are complementary to the target RNA sequence. The chemical modifications are critical because unmodified RNA and DNA rapidly degrade by cellular nucleases. Natural DNAs /RNAs (Figure 1) are made of four nucleobases (green), sugar rings (blue) and phosphate interlinkages (red). In most of the ASO drugs, either the sugar or the interlinkages or both have been modified to improve the stability and potency. There are dozens of chemical modifications available and Figure 1 shows some of the important ones. For example, the 2’-hydroxyl as well as the phosphorothioate modifications improve nuclease resistance; while the locked nucleic acid (LNA) modification increases target RNA binding affinity. The morpholinos are neutral derivatives where both sugar and interlinkages have been chemically modified to provide long term stability, efficacy, low toxicity and specificity. The drug Spinraza has both phosphorothioate and 2’-OH modifications, whereas ExonDys 51 is a morpholino derivative.

Antisense Structural Types

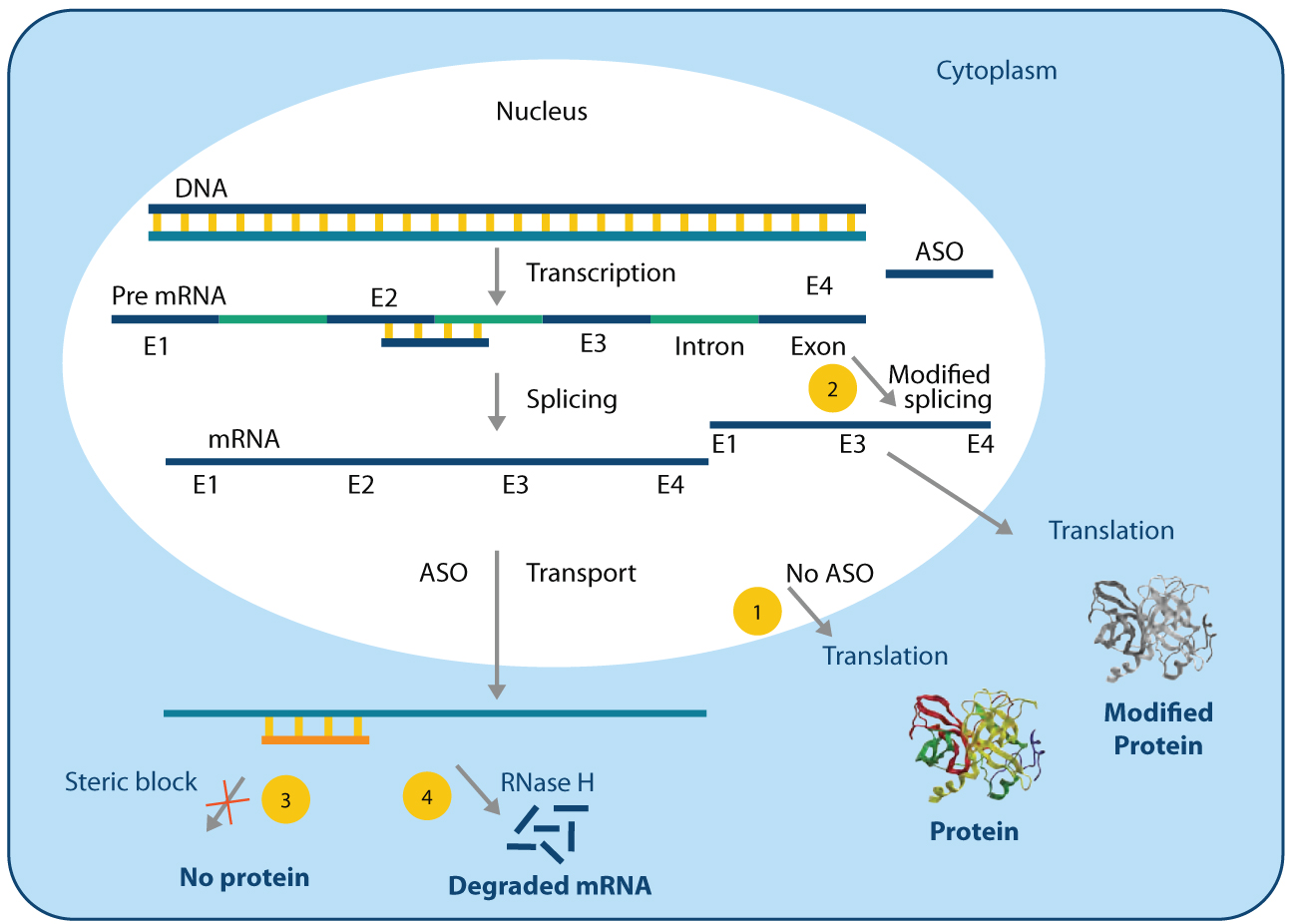

There are several mechanisms by which ASOs modulate gene expression5 . Some of the common mechanisms have been summarized in Figure 2. In the cell, DNA transcribes to the pre mRNA that undergoes further processing, known as splicing, to form the mature mRNA. The mRNA subsequently gets templated by the polymerases to translate the protein (Figure 2, Item 1). However, when the ASO is administered, it hybridizes with the complementary RNA and alters the downstream outcome. For example, when the ASO binds to the splice-junctions, it triggers alternative splicing resulting in a splice variant protein to be translated (Figure 2, Item 2) having possible therapeutic benefit. In another mechanism, ASOs can block the protein translation machinery by creating steric block at the start site (Figure 2, Item 3), thereby inhibiting protein synthesis. In addition, when a DNA-based ASO is used, the resulting duplex become susceptible to ribonuclease H (RNase H)- mediated degradation and the mRNA is destroyed (Figure 2, Item 4).

Advantages and Challenges

ASOs belong to a class which falls in between small molecule drugs and biologics but are more straightforward to conceptualize because they are based on predictable Watson-Crick base pairing. Since ASOs are chemically synthesized, GMP-grade scale up is also more feasible compared to many cell/ biologic therapies. While small molecule drugs mostly interact with protein targets (e.g., receptors, hormones, ion channels), ASOs are designed to bind RNAs, thereby significantly expanding the therapeutic target space. However, no drugs are perfect, and neither are ASOs. The biggest disadvantages of ASOs are inefficient delivery, poor pharmacokinetics and possible off-target toxicity, although research has shown that these challenges could be managed if not eliminated. Additionally, most ASO drugs have been approved for rare diseases that affect a handful of people, but still have required millions of dollars in clinical studies. Pharma companies are thus faced with a major challenge of figuring out how to make profit while keeping it affordable to patients. For instance, the first dose of Spinraza costs $750,000 for the first year and $375,000 in the subsequent years in the USA.

What Syngene can offer?

Oligonucleotide-based drugs are going through a renaissance 4 . While preparing this article in November 2019, the FDA approved another such drug Givlaari (givosiran) to treat a rare genetic condition called acute hepatic porphyria, making it the sixth approval in last four years (after defibrotide, eteplirsen, nusinersen, inotersen, and patisiran). This unprecedented fervour is steadily surging the demand of oligonucleotides for clinical uses worldwide. According to a recent estimation (April 2019), the oligonucleotide synthesis market is expected to be almost double by 20246 . While the supply pipeline is getting ready to cope up with the increased need, especially for cGMP grade oligos, consumers are facing extended delays. To help customers accelerate, Syngene offers in-house process development, cGMP manufacturing and end-to-end analytical services for oligonucleotides. The Syngene oligo facility is fully equipped with world-class DNA synthesizers, sophisticated purification and analytical instruments and highly qualified personals to satisfy all client needs, be it natural DNA/RNA, siRNA, antisense oligo, aptamer, miRNA or oligo-conjugates. Syngene is excited to offer itself as the one-stop-solution for all types of oligonucleotide needs.

About the author