Tech transfer sounds like a handover, but in a CDMO, it is a stress test. A process that behaves in a bench hood can shift when it meets plant-scale mixing, utilities, sampling routines, and tighter execution windows. The scale-up trap shows up when teams assume the recipe will scale, then discover late that heat transfer, mass transfer, and hold times changed the outcome. Strong chemical process development keeps the transfer grounded in evidence, so manufacturing starts stable instead of getting fixed batch by batch.

Tech transfer CDMO: where lab-ready is not plant-ready

During tech transfer at a CDMO, the sponsor’s intent must be translated into a process that is repeatable, auditable, and resilient to normal manufacturing variability. Many development packages are complete only for the lab that created them. A different solvent grade, a different filter area, or a different sampling quench can shift impurity formation and clearance, and it is not always obvious upfront.

A practical starting point is to define success at scale, including target yield, impurity profile, throughput, and ranges for critical process parameters. Then, chemical process development can map what must remain unchanged, what can change, and what proof is needed before a change is accepted.

Chemical process development pitfalls that create the scale-up trap

Scale-up failures in small molecules rarely arrive as one dramatic event. They appear as slow filtrations, unstable phase splits, uncontrolled exotherms, or an impurity that was minor in the lab but becomes dominant at scale. Chemical process development should treat these as design signals, not as noise.

Mixing and thermal realities that were never tested

Stirring speed and addition rate do not translate linearly across vessels. Local concentration spikes can create different impurity families, especially for fast reactions. Heat removal can become limiting, which changes kinetics and sometimes selectivity. Transfer readiness improves when scale-down models reproduce the plant’s constraints, then those models are used to set operating limits that operators can execute.

Workups and isolations that are sensitive in disguise

Quenches, solvent swaps, extractions, and crystallizations are common pain points. A lab method can look robust while being sensitive to water content or hold time. Filtration and drying can shift particle size distribution, which affects downstream handling. During transfer, narrative instructions like “add slowly” are not enough; a tech transfer CDMO needs quantified sensitivity data, clear endpoints, and defined hold-time limits.

Analytics that arrive late

A process is only as controllable as its analytics. If methods are not stability-indicating, or if sampling and sample preparation are not harmonized across sites, transfer turns into a debate. When method transfer is rushed, hidden peaks, carryover, and instrument variability are discovered during manufacturing, which is a poor place to troubleshoot.

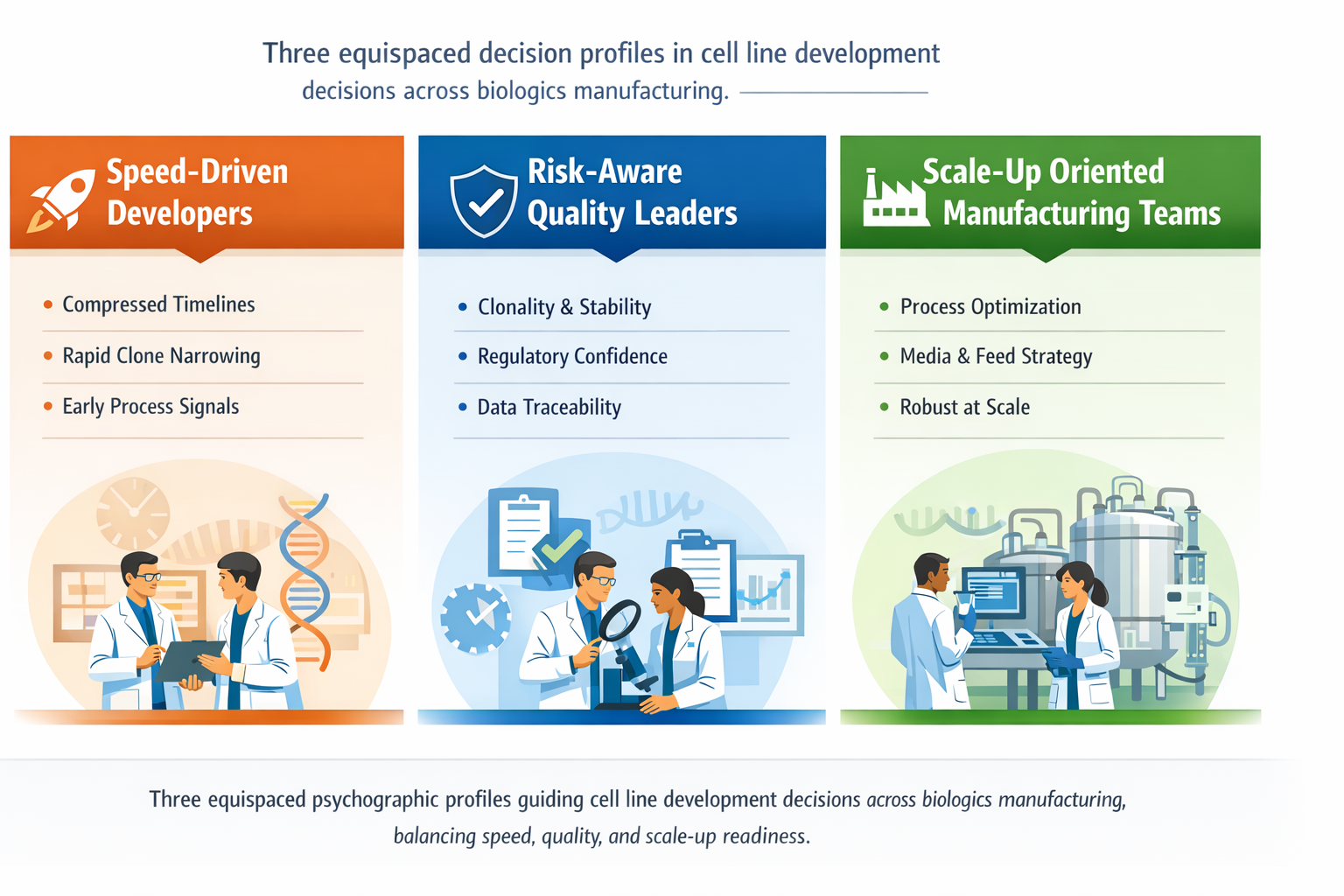

Biologics tech transfer: the same trap, more moving parts

Biologics tech transfer carries the familiar transfer challenges, plus biology. Cells respond to subtle differences in media, gases, shear, and sensor calibration. Proteins are sensitive to pH, temperature, and interfaces, so small shifts in mixing or hold conditions can change aggregation, charge variants, and glycosylation.

This is why biologics process development relies on scale-down models that reflect the large-scale environment, then uses those models to map the link between process parameters and quality attributes. Matching setpoints helps, but matching outcomes protects the product.

Biologics process development: upstream translation

Oxygen transfer, power input, and feed strategies change across scales. Control loops behave differently, and sensors can drift. In biologics process development, define equivalence using growth profiles, metabolic markers, titer, and a quality fingerprint, instead of chasing setpoints alone.

Downstream trains amplify upstream variation

Chromatography, filtration, viral clearance, and concentration steps are linked. A shift in harvest quality, such as higher host cell protein load, can stress the downstream train and erode clearance margins. In biologics tech transfer, stress testing around resin drift and filter capacity helps build a control strategy based on real failure modes.

Process knowledge management: making transfer repeatable

Even good development can fail if knowledge is not packaged for use. Process knowledge management keeps decisions consistent across teams and time, and reduces the risk that key learning sits in emails or in someone’s notebook.

What a transfer-ready knowledge set should include

The most useful package ties intent to evidence. It records why key conditions were selected, what failed and why, what critical quality attributes were identified, and which parameters truly matter. It also captures raw material attributes that drive variability, assumptions behind scale-down models, and a short list of items that should not change without impact assessment.

Avoiding the scale-up trap without slowing delivery

Avoiding delay does not mean skipping science; it means sequencing it so transfer decisions are made with the right evidence.

First, align the sponsor and site on a risk-based plan, including what will be proven in scale-down studies, what will be proven in an engineering run, and what must wait for process performance qualification. Second, build first-time-right batch documentation, with critical steps, in-process controls, and hold-time limits that reflect plant operations. Third, treat analytical readiness as a gate, not as a parallel activity that can be closed later.

In many programs, adopting a systemic approach to tech transfer helps keep upstream, downstream, analytics, and quality aligned on one narrative. It also supports integrated development services, where process, analytics, and scale considerations are handled together rather than as disconnected handoffs.

A simple readiness test

A practical test is whether the process is understandable enough to be controlled by someone who did not develop it. If the answer is yes, the transfer is likely to behave. If the answer is no, the transfer becomes a gamble. A tech transfer CDMO reduces that gamble by insisting on a credible scale-down model, a control strategy tied to critical quality attributes, and a knowledge package that supports day-to-day decisions.

When chemical process development and biologics process development are treated as living systems, not static recipes, scale-up becomes more common. It will never be perfect, but it becomes manageable, and that protects both timelines and product quality.